Day 6

Friday May 23rd

Verdun 25km

Never get off the bike.

I don’t remember why we began this ride. If ever there was a reason.

The Western Front is a realm that defies reason - a corridor of madness, a long, winding ribbon of insanity, a yellow brick road stained blood-red with shame, The Great Oz safely concealed behind his curtain of Imperialism, cranking a meat grinder of smoke, medals and mirrors, numbing dull drone of wheels spinning on mile after mile of deception and propaganda, we pass through poppy fields of lies, buried emotions, contorted realities and temples to false gods. The air thickens, turns metallic, colder - we descend ever upwards into the bad brown moonscape they call Verdun.

The wasteland.

The entire Western Front should have been left as it was.

I am sick to death of using my imagination. This land is full of deceit. This gently undulating countryside, sun-dappled yet strangely empty. Geometric rows of crosses. Softly waving flags. Neatly mown grass.

Perfectly palatable.

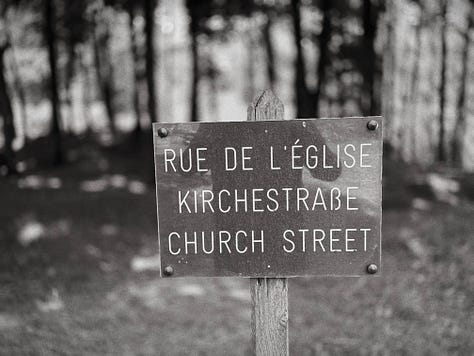

Only in the woods does the truth whisper - dark shadows, writhing vegetation. The light folds differently here. The trees don’t grow straight - they watch. The soil too fertile, alive with death.

Here, the dead do not lie still.

But if they’d had the courage, the integrity to just leave it.

Barbed wire. Shell holes. Fields of bones. Trenches full of contorted, broken dead. No man’s land. Rusting tanks. Unexploded bombs. Broken, accusatory trees. The rotting skeletons of aircraft. Rusting howitzers. Leather boots, the bones still inside.

Fuck the museums.

Fuck the visitor centres, the carparks and the manicured cemeteries. Let the coachloads of school children leave broken, sobbing, tormented. Then try recruiting them for your wars.

To educate children truthfully would be to scar them. A consent form no parent would ever sign.

What mustard gas does - the slow drowning in your own fluid.

What a flamethrower does – not just to its victim, but to the one who wields it. To live with the smell of burning flesh in your nostrils.

To kill a man with a bayonet - how many thrusts does it take as you look into his eyes? An intimacy that can never be broken no matter how many years pass.

The effect of a high-velocity bullet on flesh, on bone.

Violence depends on denial. Objectification. In both domestic and ‘legitimised’ combat. That’s why your partner becomes a ‘crazy bitch,’ why your enemy becomes a ‘towelhead’ or a ‘bad guy.’ You can’t beat your wife if she’s your beloved, can’t kill a man if you see his humanity. It must be erased.

After World War II, someone (with a vested interest, no doubt) calculated the number of bullets fired versus actual enemy kills. Only 15–20% of US frontline riflemen fired their weapons. And many aimed to miss. Unconsciously, they refused to kill.

So, someone else (with a vested interest, no doubt) changed the targets. No longer bullseyes, they used human silhouettes. By Vietnam, kill rates had risen to over 90%.

So too had PTSD.

I’ve deliberately avoided much of the poetry read aloud with calculated and rehearsed solemnity on Remembrance Sunday. But today, standing before Fort Vaux, shrine to unimaginable suffering, we read Wilfred Owen, and a poem he crafted whilst resident at Craiglockhart War Hospital in Edinburgh where he had been consigned for treatment for neurasthenia, or ‘shell shock’ as PTSD was then known.

Dulce et Decorum Est by Wilfred Owen (1893-1918)

Bent double, like old beggars under sacks,

Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge,

Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs,

And towards our distant rest began to trudge.

Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots

But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame; all blind;

Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots

Of gas-shells dropping softly behind.

Gas! GAS! Quick, boys! An ecstasy of fumbling,

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time;

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling

And flound’ring like a man in fire or lime.

Dim through the misty panes and thick green light,

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.

In all my dreams before my helpless sight,

He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.

If in some smothering dreams you too could pace

Behind the wagon that we flung him in,

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,

His hanging face, like a devil’s sick of sin;

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues,

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori.

It was at Craiglockhart that Owen famously met fellow war poet and mentor Siegfried Sassoon. A decorated war hero, Sassoon had been hospitalised to save face following the publication in The Times on July 31, 1917, of a letter titled A Soldier’s Declaration.

“I am making this statement as an act of wilful defiance of military authority, because I believe that the war is being deliberately prolonged by those who have the power to end it.

I am a soldier, convinced that I am acting on behalf of soldiers.

I believe that this war, upon which I entered as a war of defence and liberation, has now become a war of aggression and conquest.

I believe that the purposes for which I and my fellow-soldiers entered upon this war should have been so clearly stated as to have made it impossible to change them, and that, had this been done, the objects which actuated us would now be attainable by negotiation.

I have seen and endured the sufferings of the troops, and I can no longer be a party to prolong these sufferings for ends which I believe to be evil and unjust.

I am not protesting against the conduct of the war, but against the political errors and insincerities for which the fighting men are being sacrificed.

On behalf of those who are suffering now, I make this protest against the deception which is being practised on them; also I believe that I may help to destroy the callous complacence with which the majority of those at home regard the continuance of agonies which they do not share, and which they have not sufficient imagination to realise.”

He should have got the Victoria Cross for such courage.

Instead, he was declared ‘mentally unfit’. A performance that achieved madness.

Dulce et Decorum Est was not published until after Owen’s death, too contentious an inditement as it was in a time of war, too honest, too real. Too savage.

But what are the Great War poets if not messengers of truth, much like the Fool in the medieval courts, the one true voice whose job it was to keep the Regent from becoming tyrannical?

And where is the Fool now, when perhaps we need him the most, as missiles and drones rain down in Iran, Ukraine, Israel, Lebanon? A thousand-thousand firework displays for the hollow men who press the buttons for profit and power.

Parsifal, hero of the Grail Quest, means ‘pure fool’ in Old German.

Parsifal is Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz, Chas in Performance, Luke Skywalker in Star Wars, Willard in Apocalypse Now, the naïve seeker in each and every one of us.

Parsifal sees the Grail but cannot understand. Not yet. He must lose everything first. Only then may he return.

I first came to the Western Front thirty years ago and it’s taken until now to even begin to unravel the complexity of what it awakened within me.

This was always going to be much more than a bike ride.

The others wander over the broken mound of Fort Douamont, its turrets and emplacements still mostly intact, sepulchre to those who died within by gas, flame and bayonet. I take myself off alone down a path into the forest, the writhing undergrowth a turbulent, calcified sea, the shell holes and trench lines still as defined as the day they were gouged into these hills.

No peace shall return to these dark glades.

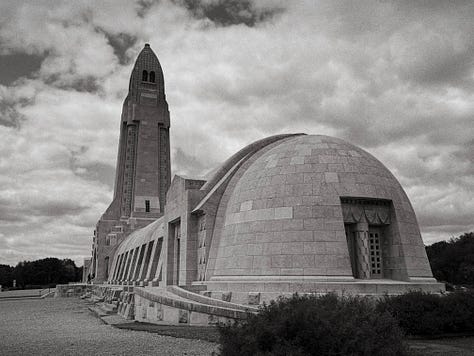

Later, at the ossuary containing the bones of one hundred and twenty thousand men, I stare through one of the windows into the empty sockets of skulls. They stare back. Not grinning. Not symbolic. Just… watching.

This is the dead land. This is cactus land.

There are no metaphors at Verdun. I am looking through a glass darkly into the shadow of a world gone insane.

Never get off the bike.

Absolutely goddamn right.

Unless you are going the whole way.